The Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtable Guy von Dardel Memorial Meeting Budapest May 20-21 2016 Stockholm 13-15 September 2017 Complementary text 2019

Bo Theutenberg,

Ambassador (ret), Professor of International law Former Chief Legal Adviser to the Swedish Foreign Ministry

Sweden’s Social Democratic legacy that sealed Raoul Wallenberg’s fate – Gordievsky’s book ‘A blind mirror’

In order better to understand the title of my presentation, I must give some background information. It is a challenging title dealing with the core of Sweden’s Social Democratic Party’s policy in relation both to the Soviet Union and “the West”, including NATO and the United States. Raoul Wallenberg, born August 4, 1912, was only 32 years old when he, as a Swedish diplomat, on January 17, 1945 was detained by the Soviet military forces advancing towards Budapest – and then disappeared into the Stalinist prison system characterized by total lack of justice and respect for human lives. Although the Soviet Union (later Russia) maintained that he had died on July 17, 1947 in Moscow’s notorious Internal (Lubyanka) Prison – which also served as headquarter for the Soviet State Security Services, (NKVD,

SMERSH and MGB/KGB.– nobody knows his real fate. What a nightmare for his parents and his relatives, to live with the loss and the uncertainty, decade after decade.

When I myself, 24 years old, joined the Swedish diplomatic corps as an attaché in 1966, I did not know very much about Raoul Wallenberg. When I was sent to work at the Swedish Embassy in Moscow, as a First Secretary, between 1974 and 1976, I became more and more interested in Raoul Wallenberg’s fate. Frequently I passed by the Lubyanka Prison, always paying silent tribute to this fellow-diplomat, who – as I gradually came to understand – was totally abandoned by his own employer, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (UD), and his own government.

At the time of his disappearance in January 1945, the wartime four-party coalition under the Social Democratic leader Per Albin Hansson was still in office, with the career diplomat Christian Günther as Foreign Minister. After the end of World War II, this coalition government was replaced on July 31,1945 by a pure Social Democratic government with Per Albin Hansson as Prime minister and Professor Östen Undén as Foreign Minister. After Per Albin Hansson’s sudden death on 6 October 1946, the newly elected Social Democratic leader Tage Erlander succeeded him as Prime Minister. Östen Undén served alongside Erlander as Minister for Foreign Affairs, the post he kept for seventeen years, until 1962.

Actually Undén was also the Chief Legal Adviser in International law at the Foreign Ministry (UD:s Folkrättssakkunnige), which post he held for twenty-six years (1920-1924 and 1946- 1961). For almost seven decades (1919 – 1987) this was an important and independent position at the ambassadorial level, attached directly to the Offices of the Foreign Minister and the Secretary General of the Foreign Ministry (UD:s kabinettssekreterare), to whom the Chief Legal Adviser reported.

I myself was serving as the Ministry’s Chief Legal Adviser in international law for a decade (1976 -1987), when I in 1987 resigned from the post, as a protest against what I considered the Social Democratic government’s pro-Soviet policy. I could not let my name be connected with the Swedish Government ́s “policy of indulgence” towards the Communist Soviet Union. Therefore I chose to resign. The soft or even non-existent Swedish reaction to Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance in 1945 was an integral part of the general “Swedish paralysis” in

relation to the Soviet Union.

It is the Foreign Minister (and the Chief Legal Adviser) Östen Undén that has had to bear the heaviest accusations and criticism for not doing enough to help his own employée (Raoul Wallenberg) in light of the Soviet Union’s unacceptable treatment of a Swedish diplomat and for not pursuing a harder line against the Soviet leadership. Undén has been accused of initiating the so called ”policy of accommodation” (Eftergiftspolitik) towards the Soviet Union; that is say, to do nothing that could provoke or upset Stalin and the Soviet Union. He became the “founding father” of Sweden’s strict policy of neutrality, which instead – somewhat ironically – was characterized by a close secret military and intelligence cooperation with Western powers. I know this first-hand, since I served in the military forces during the years 1965- 1988.

Although formally neutral in times of war, Sweden would in fact cooperate closely with the United States and NATO. This was the real truth behind the Swedish official declaration of neutrality, which of course led to great Soviet suspicions against Sweden’s officially neutral status. Even though a close military cooperation between Sweden and the United States came to develop from 1952 and onwards, Soviet suspicions of planned future Swedish-U. S.- cooperation could have influenced the Soviet detention of Raoul Wallenberg in Hungary already in January 1945. The rumoured accusations of espionage may have been a contributing factor to rendering Sweden “mute” in its first reactions to Stalin and the Soviet Union when trying to find out Wallenberg’s fate after his detention in 1945 (see below).

In 1976, fourteen years after Östen Undén’s resignation in 1962, I was myself appointed to the post as the Chief Legal Adviser to the Foreign Ministry. Since I also had a parallel military career, with regular service in the Swedish Air Force, and – from 1976 onwards – at the Defence Staff (Operational Section Op 2 that also handled intelligence matters during that time), I had an excellent insight into the extremely sensitive intelligence sphere, not least in relation to the Soviet Union and its espionage and intelligence bodies, like the KGB , GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate, Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye), the International Department of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) Central Committee and so forth. I knew quite a lot about Soviet espionage, infiltration and disinformation during the Cold War, which was as heavy as it is today under the current Putin regime.

The remarkable double standards of the so-called Swedish neutrality – both “neutral” and “non-neutral” – “allied” and “non-allied” – led to extreme caution in all Swedish actions in relation to the Soviet Union, often even to a total stand-still, where Sweden did not dare to express itself in any firmer way. A too strong position on various matters – including a demand for clarification of the disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg – could have led to the disclosure of Sweden’s difficult strategic and military position.

This muted policy resulted in what I would call a Swedish “non-position” with regard to a possible Swedish participation in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). In 1949, two of Sweden’s neighbours, Denmark and Norway, became founding members. At the same time, Stalin had forced Finland into the 1948 Friendship- and Cooperation Pact with the Soviet Union, which lasted until 1992. Even though the United States and NATO helped Sweden to build up its military defence into one of the strongest forces in Europe, Sweden (or rather Foreign Minister Östen Undén) did not dare to officially join the Western Defence Pact. This total paralysis in relation to NATO has continued for 70 years, still making it impossible for Sweden formally to choose NATO – for fear of incurring “Russia’s revenge”.

During my decade as the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s Chief Legal adviser (1976-1987), I participated in the management of nearly all crises that occurred during that time, mostly involving Sweden and the Soviet Union. I helped manage the incident involving a Soviet submarine U 137 in October-November 1981 in the Karlskrona archipelago, as well as responding to the Soviet submarine activities in Hårsfjärden in the Stockholm archipelago in October 1982. Among other things, I authored the text of the two official notes that were handed over to the Soviet Ambassador on November 5, 1981 and April 26, 1983 respectively,

protesting against these intrusions into Swedish territory. During 1985-1987, I also led the exploratory talks with the Soviet Union concerning the delineation of the Economic

Zones east of Gotland in the Baltic Sea (the so called ”White Zone Area”), which led to a number of incidents during the years before the matter was resolved.

Thus I had a first-row seat regarding the tensions that existed between Sweden and the Soviet

Union. On some occasions the unresolved matter of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate entered into the management of the Swedish-Soviet crisis. I am mentioning one of these occasions in Volume 1 of my memoirs Dagbok från UD (“Diaries from the Foreign Ministry”), which is based on my daily diaries.

In my notes, I describe the heated conversation between the Swedish Foreign Minister, Ola Ullsten (Liberal party), and the Soviet Ambassador Mikhail Jakovlev in October 1981, when a Soviet submarine had run aground in Swedish internal waters, outside of Karlskrona. The conversation was directly related to the troubling indications that the stranded submarine had nuclear missiles on board. Right here – just in the midst of the discussion about nuclear weapons on board the submarine – I make a special point in my diaries to underline that it was suggested by some parties that Sweden should utilize the submarine U-137 and its crew in a bargain to have Raoul Wallenberg released – or at least to utilise the detained submarine to press for further information about the fate of Raoul Wallenberg. This occurred in 1981, which meant that Raoul Wallenberg, if he was still alive, would have been 69 years old.

It is exactly this note in my diaries – which are written in Swedish – about the possibility of an exchange between the Soviet submarine and Raoul Wallenberg that gave reason for Susanne Berger to contact me regarding the Swedish reasoning behind the idea of an exchange and what happened to this idea. Her first email to me asking these questions is dated 12 November 2014, about the same time as she published the report “An Inquiry steered from the Top?, Twenty-five years later, still many loose ends in three major Cold War Cases”?”, analysing the shortcomings of the research so far made within the sphere of “lost Swedes in Soviet prisons “. It is not only Raoul Wallenberg that was lost in the Soviet/Russian detention camps and prisons, but also other Swedes, like crewmembers of fishing boats that disappeared in the Baltic. She also mentioned that she had been working as a consultant to the Swedish- Russian Working Group that investigated the case 1991-2001, a most important document.

As early as 1990-91, an international commission, led by Raoul Wallenberg’s half-brother, Professor Guy von Dardel, working closely with Russian experts and officials, was able to confirm that both Raoul Wallenberg and his driver Vilmos Langfelder had been imprisoned in the Soviet Union during the years 1945 -1947. They were both brought from Budapest to Moscow in January 1945.

Later, a bilateral Swedish-Russian Working Group that investigated the Wallenberg case from 1991 until 2000 managed to expand on these findings, but concluded its investigation without obtaining full clarity about Wallenberg’s fate. Unfortunately, many of the documents released by the Russian side of the Working Group were heavily censored and important collections remained altogether inaccessible for most researchers. Among other things, these documents raise the important question if Raoul Wallenberg could have been held as “Prisoner no. 7” in the Lubyanka Prison in 1947; and if he possibly remained there some time after July 17, 1947, his alleged date of death, according to Soviet authorities. The whereabouts of “Prisoner no 7” has then become a main factor for the continuous Wallenberg research.

Upon receiving Susanne Berger’s email on 12 November 2014 I informed her about the background of this “short episode” that occurred on 2 November 1981 where Raoul Wallenberg’s name popped up in the midst of the acute crisis management of the Soviet submarine.

Should Sweden choose to involve Wallenberg into the crisis management, which already was extremely dangerous and complex and really could have led to an armed confrontation between Swedish and Soviet military forces, the latter prepared to penetrate into Swedish waters and release the submarine by force? I felt at the time that some effort should be made nevertheless to press the Soviet side for information about Wallenberg’s fate, even in this difficult situation. However, the Swedish Foreign Ministry decided that the question of Wallenberg’s fate should be pursued strictly through official diplomatic channels.

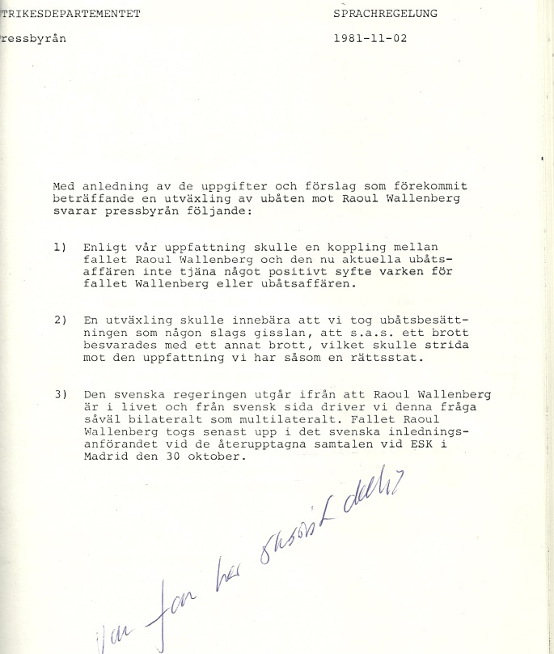

I noted this statement in my diary:

‘Absolutely not, says the Swedish Foreign Ministry! We cannot take the submarine and its crew hostage, meaning we cannot counter one violation (taking Wallenberg) with another (taking the submarine hostage). This supposedly goes against the idea we have of ourselves as a society based on laws’, it is

stated pompously. Who the h-ll has written this?” [Fig. 15]

As my frank comment shows, I did not agree with the official position taken by the Ministry’s Legal Department (which obviously had written this ill-formulated paper), ”to do nothing”. [Fig.1]

Fig. 1. Official internal ”Talking Points”(Sprachregelung) issued by the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s Press Department in 1981, rejecting requests to use the incident of a stranded Soviet submarine outside of Karlskrona to elicit information about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate from the Soviet government. The copy shows a handwritten note by the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s Legal Advisor at the time, Bo Theutenberg, who strongly disagreed with the decision. The note reads: ”Who the h..l has written this?”

This was the general trend in the Ministry when it was led by Social Democratic ministers, who, as I said earlier, became ideologically muted or downright paralyzed with regards to everything that pertained to the Communist Soviet Union, a country that many of them really liked, as they also basically liked the Marxist-Leninist or Communist ideology that was the basis for the existence of the Soviet Union.

This was, for instance, very much the case for the former Swedish Foreign Minister Östen Undén, who must be described as quite left on the ideological spectrum. His wish/hope was to serve as a kind of “bridge-builder” between East and West, creating a ”middle way” between communism and capitalism. Consequently, he was not pleased to encounter obstacles to such a noble cause, preventing him to pursue the creation of this new ”middle way”. The strange thing is that he did not recognize the advantages of democracy and thus regarded the two systems as alike. In Swedish we refer to this as “kålsuparteorin” (“cabbage soup theory”) – which suggests that one system is as good as the other.

One really feels chilling fright upon discovering that Östen Undén basically viewed the Raoul Wallenberg as such an “unwanted obstacle” in his way. When, for instance, Undén for the first time met the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov at the United Nations in New York on November 21, 1946, i.e. when Wallenberg was still alive in the Soviet prison system, Undén choose not to bring up the case of Wallenberg at all, a most astonishing behavior of the Swedish Foreign Minister. Instead, it was the Trade- and Credit Agreement between Sweden and the Soviet Union, an extremely generous Swedish gesture to the Communist Soviet Union, that the two men discussed.

I personally find it quite shocking that Sweden offered the Soviet Union a favorable $300 million credit at the same time as the Soviet Union had detained one of its diplomats who then totally disappeared. Especially since the Soviet Union had great difficulties obtaining much

needed credits elsewhere. Why not halt or suspend the negotiations until the Soviet Union had released Sweden’s diplomat? One could really ask!

Simultaneously, from the end of 1945 to the beginning of 1946, the disturbing event that has become known as the Extradition of the Baltic prisoners took place, which further demonstrated Sweden’s more or less total surrender to Stalin and his demand to have 167 former Baltic soldiers who were forced to fight in the German Army during World War II, extradited to the Soviet Union to receive punishment (as traitors) for their participation on the German side in the war.

This demand was made possible because of the illegal annexation of the Baltic states Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania that Stalin had carried out at the beginning of the war in 1939-1940 (according to the provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939) and – after the collapse of the German occupation of these countries in June 1944 – his bringing them once again under Soviet control. Against all rules of international law, the Swedish Government conceded rapidly to the Soviet claims regarding the Baltic States (as integral parts of the Soviet Union). This was the background when the Swedish Foreign Minister Undén met his Soviet colleague Molotov in New York in November 1946. No wonder Undén would not amongst this string of Sweden’s complete compliances with Stalin’s wishes and demands take up the matter of a Swedish junior diplomat’s disappearance in a Soviet prison!

On the Soviet side, the silence demonstrated by the leading figure of the Swedish foreign policy establishment could not be understood as anything else but a signal from Sweden to the Soviet Union that the official Swedish line already then, in November 1946, was to regard Wallenberg as dead and that the Swedish government did not wish to talk about it any longer. After reviewing Molotov’s own records from the conversation in New York with the Swedish Foreign Minister, kept in the archives of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID), the Russian side of the official Working Group studying the Wallenberg case from 1991-2001 concluded: “It seems as though [at the time] the question about R. Wallenberg did not exist at all in the Swedish-Soviet relations”. This is how Foreign Minister Undén ́s silence was interpreted by Molotov and the Soviet side: The Swedes themselves had downplayed the Wallenberg-case!

As it turned out, the choice of Foreign Minister Undén to omit mentioning of Wallenberg’s name in his private conversation with Molotov in November 1946 is unfortunate, because if he had done so, it would have been interpreted by the Soviets as a formal correction of the extremely remarkable message that Staffan Söderblom, the Swedish envoy in Moscow, delivered to the ears of Stalin on June 15, 1946. Stalin had granted Söderblom a personal farewell audience, an exceptional occurrence, as foreign envoys were hardly ever received by Stalin. Shockingly enough, at this rare occasion, Söderblom told Stalin that “he /Söderblom/ was personally convinced that Wallenberg had been the victim of an accident or the victim of robbers” (sic!). How could Söderblom know? And why on earth did he decide to give this strange message to Stalin? Söderblom was not under instruction from the Foreign Ministry in Stockholm to do so! Or was he? Was it such a remarkable message about Wallenberg’s death that the Swedish envoy in his official farewell audience with Stalin was instructed to convey?

One could really believe he was. Especially since Söderblom reported to Foreign Minister Undén about the meeting by official dispatch, detailing what he had told Stalin, namely that he had brought his sensational personal opinion about “Wallenberg’s death” directly to Stalin’s attention. When Undén met Molotov in New York five months later (November 21, 1946), he almost certainly knew of Söderblom’s remarkable message to Stalin about Wallenberg’s “death by accident or robbery”.

Because of his knowledge of Staffan Söderblom’s message to Stalin, Foreign Minister Undén should have immediately corrected the impression left by Söderblom in his (Undén’s) subsequent talk in New York with Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov, if he had wished to do so. But he did not. He remained silent. Therefore, the Soviets interpreted Söderblom’s message to Stalin in June 1946 as the Swedish “official line”, strengthened by Undéns conspicuous silence. Obviously, the Soviet interpretation of the Swedish line of reasoning about Wallenberg was that the Swedish government considered him as dead (by accident or robbery). However, in order to keep a clear conscience and for the sake of Wallenberg’s family, Swedish officials had to continue to make official inquiries about his fate. And the Soviet side knew how to respond. That is how Soviet representatives in 1946 interpreted the Swedish remarkable and most peculiar handling of the Wallenberg case. It was, as it seems, the Swedish diplomatic game around Wallenberg that actually killed him.

A conclusion of this kind seems all the more reasonable when also taking into consideration Söderblom’s even more peculiar (or shall I even say close to insane) earlier message – on December 26, 1945 – to A.N.Abramov, head of section at the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who took formal notes of Söderblom’s statements. Abramov’s account of his exchange with Söderblom stayed undiscovered in MID’s archive for nearly 60 years until the Swedish-Russian Working Group came across the documentation as part of their formal investigation. The public, therefore, learned of Söderblom’s disastrous conversation with Abramov only in January 2001.

According to Abramov’s account, Söderblom had not only conveyed the message that Wallenberg “was dead by accident or robbery” but, in addition to that, he had also delivered a personal appeal to Soviet government, outlining how it ought to respond to the continuous official Swedish inquiries in the case. It would be ”splendid”, Söderblom told Abramov, if the Swedish Legation in Moscow could receive an official Soviet response, namely that Wallenberg had been killed (in an accident or by robbery.) Söderblom then added “that this was necessary primarily because of Wallenberg’s mother who still believed that her son was alive and used all her strength in the search for her son.” With that, Söderblom had even surpassed the message he was going to deliver to Stalin personally six months later (at the audience of June 15, 1946).

The Swedish Envoy dispatched a short report on January 3, 1946 to the Swedish Foreign Ministry about his meeting with Abramov. Even though he does not mention his personal appeal to Abramov (about the Soviet handling of the matter), the Swedish Ministry as well as Foreign Minister Undén knew very well what kind of message Söderblom had conveyed , namely that “Wallenberg was dead”. And Foreign Minister Undén – nor anybody else – did anything to change this fateful message to the Soviet Union.

Söderblom’s behavior is especially upsetting since it is known that at the very moment as Söderblom delivered his “death sentence” of Wallenberg to Abramov (“please tell us officially that he was killed … then we can continue our good relations …”), Wallenberg was held in the Lefortovo Prison in Moscow, only a few blocks from MID.

Finally, in August 1947, the Soviet Deputy Foreign MinisterAndrey Vyshinsky declared in an official note that Wallenberg was unknown to Soviet authorities and that he was not found ”on the territory of the Soviet Union”. This was of course a lie, which the Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Gromyko conceded in a message to the Swedish government ten years later.

In February 1957, Gromyko announced that Wallenberg had been held in Soviet prisons for more than two years. However, according to a note signed by Dr. A.L. Smoltsov, head of Lubyanka Prison’s medical service – Wallenberg died suddenly in his cell on July 17, 1947).

As, however, indicated above, the possibility that a “Prisoner no 7” interrogated on July 22- 23, 1947 could well be identical with Raoul Wallenberg, in many ways questions the credibility of the Gromyko Memorandum of 1957. It opens up the possibility that Wallenberg may have survived his initial prison detention. At least the questions about “Prisoner no 7” are spreading serious doubts that somehow must be dispelled.

To my mind, the extraordinary concession from the Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Gromyko in 1957 about earlier Soviet lies (i.e. the Vyshinsky note of August 1947), should be seen in the light of Prime Minister Tage Erlander’s official visit to Moscow in March 1956, during which the Wallenberg case was brought up on the highest official level. It is not the first time that Prime Minister Erlander rebuked his Foreign Minister and took the lead over Undén’s doctrinal and legalistic approach to everything that happened around him. Here it must be emphasized that the utterly top secret military and intelligence cooperation that Sweden clandestinely started with the United States and other Western powers in 1952 mainly was worked out and expanded without Foreign Minister Undéns knowledge. He was thus kept away from essential elements of Sweden’s military security policy, where he himself was advancing the strictest possible legalistic interpretation of Swedish neutrality, with the precepts of international law as the sole loadstar for the behavior of all states, including the Soviet Union. Needless to say, this was a very strange idea to both Stalin and Vyshinsky. Obviously neither of them was on the same legalistic platform as the Swedish Foreign Minister, who really believed that “law governs countries”. Therefore the Swedish Foreign Minister was just plainly cheated and outmaneuvered by Stalin and his henchmen.

Considering the Swedish Prime Minister Tage Erlander’s official visit to the Soviet Union in 1956, it should be said that when studying the case of Raoul Wallenberg in all available Foreign Ministry and other governmental papers, it seems obvious that the case would have

been far better off in the hands of the enterprising Prime Minister who obviously did not consider himself restricted by his own Foreign Minister’s strange attitude to the case. The Prime Minister boldly raised the Wallenberg case in the halls of the Kremlin, in spite of unofficial Soviet warnings beforehand not to do so. The same could be said about the Social Democratic Secretary General (kabinettssekreterare) of the Foreign Ministry 1951-1956 Arne S. Lundberg, who engaged himself actively in the Raoul Wallenberg case.

Even though the Swedish-Russian Working Group of the 1990s saw no reason to distrust the authenticity of the veracity of Mr. Abramov’s notes contained in MID’s Archive regarding his conversation with the Swedish envoy Staffan Söderblom on November 26, 1945, (it should then really contain a true version of Söderblom’s more or less insane message to Abramov) there are of course “hardliners” that would never ever trust any kind of Soviet/Russian message/account regarding Wallenberg as containing any kind of truth.

Over the years, some observers interpreted the Soviet ambiguous and often contradictory messages regarding Raoul Wallenberg as a position taken for the purpose of utilizing Wallenberg in some form; possibly to recruit him for their interests or to use him in one of the many spy exchanges that were taking place during the Cold War period. The Soviets could very well have kept Wallenberg for an indefinite period of time, in order to utilize him to protect some dominant Soviet interest that suddenly was jeopardized, due to unexpected events, like the arrest of Swedish Air Force Colonel Stig Wennerström as a Soviet agent in June 1963 or the grounding of the Soviet submarine U 137 on October 28, 1981.

Many other nations, including Switzerland, had succeeded in carrying out such exchanges. Why not Sweden? Was Sweden, with its high moral values, too moralistic and legalistic to involve itself into such dirty human trade? Tragically, even if the Russians after some years really would have liked to release Wallenberg and send him home, this was impossible because of all the official lies that they had produced over the years in order to conceal the real truth about him.

Coming back to the “Sprachregelung” (Talking Points) dated November 2, 1981 itself (see the illustration above), it is interesting to note that it expressly states that the Swedish government at the time held the official view that Raoul Wallenberg still was alive. The Swedish Government obviously did not entirely trust the official Soviet messages of Wallenberg’s death in July 1947. Also, the text emphasized that the Swedish government was “pursuing the matter both bilaterally (with the Soviet Union) and multilaterally”. As mentioned above, if Wallenberg was alive at that time, he would have been 69 years, well within the range of normal life expectancy.

It should be emphasized here that the Swedish government’s position that Raoul Wallenberg could be alive was basically a legalistic one. In the absence of complete and convincing evidence for his death, Swedish officials had to take the position that he could be alive. But if Sweden had such doubts or rather because of the absence of evidence, Sweden should have done the only effective thing, namely to bargain with the Soviets about him in a serious way.

However, it is still the old moralistic attitude that prevails in the wording of the “Sprachregelung” (see above).

In spite of my position as the Chief Legal Adviser of the Ministry and even Professor of international law it was this moralistic and legalistic hypocrisy that I reacted against, as evidenced by my notation on the document, “Who the hell has written this?” Most probably also my military and partly my intelligence background made me take a more realistic attitude towards any possibility, however slim it might have been, to save Wallenberg or at least to utilize the stranded submarine to gain more information about his fate. “We give you the sub – you give us Wallenberg”! Everything should be done to save a life! Of course it is not for Swedish diplomats or other officials to carry out such ”dirty deals” with criminal states (as the Stalinist Soviet Union was). However, representatives from the intelligence services should have explored all options.

Sweden never reached any success in the “exchange business” because of the attitudes described above. Officials representing a more hard line view in the Swedish Foreign Ministry ought to have been able to save Wallenberg’s life. Therefore the whole Wallenberg case is – as it is so correctly stated in the official Swedish report SOU 2003:18 – a “diplomatic failure”, actually the worst diplomatic failure in modern times, where above all the Social Democratic governments are to be blamed (1945-1976, 1982-1986, 1986-1991,

1994-2006, 2014- ).

It should, however, be emphasized that a certain discrepancy related to the approach to the Wallenberg case is notable between Social Democratic governments (with their more favorable inclination towards the communist Soviet Union which collapsed in 1991/) and the Non-Socialist governments governing Sweden 1976-1982, 1991-1994, 2006-2014. The Non- Socialist Governments tried at least to arrange some kind of exchange of Raoul Wallenberg and prominent Soviet spies and agents, although without success.

In 1979, when Ola Ullsten held the post as Swedish Prime Minister in a short-lived liberal government (1979-1980), with Hans Blix as Foreign Minister, a real effort was made through KGB-channels in Moscow to exchange Wallenberg for Stig Bergling, a Swedish officer who was sentenced to life imprisonment for espionage for the Soviet Union. The contact with the KGB took place in Moscow in September 1979 and was reported to the Foreign Ministry on 21 September 1979 as unsuccessful, apparently because Wallenberg by that time was dead.

It is also worth mentioning that the internal “Sprachregelung” of 1981 has never appeared before in any of the many Wallenberg investigations. This document was included in my personal archive. The Legal Adviser kept such an archive, which was not included in the general archive of the Ministry, to which access could be gained too easily by unauthorized persons. Sensitive or top secret documents – also involving military or intelligence matters – were kept in secluded archives – called the “Yellow Safe” or the “Poison Safe” – in order to prevent these from falling into the hands of foreign intelligence services, a not unlikely scenario, given the links that these foreign representatives maintained with officials in the Foreign Ministry.

It was a great risk for such documents to get into hands of persons who should not have access to them. I can of course here refer to Colonel Stig Wennerström, who worked in the Foreign Ministry. This is where he copied some of the highly secret documents that he handed over to Soviet intelligence (GRU/KGB). He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1964. There were also persistent rumors that Wennerström had assistance high up in the leadership of the Foreign Ministry, a person referred to as “Getingen” (“the Wasp”). Therefore extreme care had to be exercised in the handling of top secret documents, to which category the Wallenberg papers belonged. One never knows what kind of damage a person like “Getingen” could have done in the Wallenberg case. If “Getingen” indeed existed and was operating in the Foreign Ministry, he could very well have helped to prepare the way in favor of the most optimal solution for the Soviet Union, that is to say to place roadblocks in the path of the official investigation. But wasn’t that, in fact, actually the outcome of the whole Wallenberg case? Now Wallenberg is officially proclaimed dead. The Soviet Union/Russia has in the long run escaped the shame it would have faced if the full and awful truth of his treatment had been revealed.

Historians and other researcher must therefore be warned that the whole truth about the Wallenberg story (as for all other more complex and secret stories) is not to be found in the general archives of the Foreign Ministry. Key documents may instead have been dispersed into different hands and into personal archives, in lucky circumstances occasionally popping up in the memoirs and diaries of persons who themselves participated in the handling of these matters long ago.

In my diaries, published in four volumes between 2012-2019 under the title Dagbok från UD (“Diaries from the Foreign Ministry”) – containing my frank and unedited comments about continuous events in the Foreign Ministry, in the Government and at the Defence Staff, I come to the conclusion that the long Social Democratic grip of power in Sweden (1920-1976, 1982-1991, 2014 – still 2019 ) must be explained mainly on ideological grounds. As an ideology, Marxism-Leninism/Communism was quite well liked among the early Swedish Social Democrats, a period during which the ideological frontiers and limits were not yet so fixed between “Revolutionary Socialism” and “Democratic Socialism”. One must never forget this basic tenet when analyzing the Swedish muted position in relation to the Soviet Union, a phenomenon that remarkably enough seems to have passed on to today’s Non- Communist Putinist-Russia.

This ideological background also made it easy for the Soviet Union’s espionage and intelligence organs, like KGB, GRU and ID (International Department of the Central Committee), as well as for East German STASI (Staatssicherheitsdienst) and other East European intelligence bodies, to infiltrate with both spies and agents into different spheres of the Swedish society, even into the higher political and diplomatic strata. Many “agents of

influence” were found among journalists and mass media representatives, who willingly spread the Soviet message, along with “infiltrated agents” who carried out their job of undermining political and diplomatic circles, surely also in the Swedish Foreign Ministry.

It is in Volumes 2, 3 and 4 of Dagbok från UD I discuss in detail “the Angels of the Soviet Union” (as I call them) that came to serve inside the Swedish Foreign Ministry from the revolutionary 1960s all the way up to the present, spreading their Marxist or communist slogans. This special group of civil servants obviously also had great opportunities to steer the Wallenberg-case into a direction that would not cause too many problems in relation to the Soviet Union, later Russia; in spite of the many bona fide-diplomats that over the years have been working with the Wallenberg-case.

The historian Susanne Berger summarized this point succinctly in her review of my diaries: ”The seven decades long, almost reflexively pro-Soviet and later pro-Russian orientation of Sweden’s ruling Social Democrats,” Berger wrote, ”has irrevocably shaped the thinking of a whole generation of Swedish politicians, regardless of political affiliation.”

Coming back to the muted or even paralyzed attitude of the Swedish Social Democratic government when trying to obtain some information from the Soviet dictator Stalin just after World War II, personified by the Swedish Envoy Staffan Söderblom it is, again, worth emphasizing the poor figure that the Swedish envoy Staffan Söderblom presented in his official conversations with the Russians in 1945, immediately after the disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg.

After Stalin declared the previous Swedish envoy in Moscow, Wilhelm Assarsson persona non grata in 1943, it was not an easy task for Söderblom – the previous head of the Political Department of the Foreign Ministry – to accede to the difficult post in Moscow, especially considering his personal struggle with various illnesses and the like. He made fatal mistakes in exercising his diplomatic duties vis-à-vis Raoul Wallenberg. Even more fatal was the fact that Söderblom’s mistakes never were rectified by his superiors in the Swedish Foreign Ministry, especially the Swedish Foreign Minister Undén, who easily could have done that had he wished to do it. When he finally did it, it was apparently too late.

With regard to Foreign Minister Undén, his thinking was characterized by his ideological admiration for the Soviet Union, accompanied by a sincere desire to establish such cordial relations with the Soviet Union that Sweden could contribute to a real détente between East and West. The Wallenberg case would not be allowed to disturb this wishful thinking. That Foreign Minister Undén really held this view is confirmed by the Swedish Ambassador to Moscow Gunnar Hägglöf who succeeded Staffan Söderblom when he was recalled in 1946. In his published memoir, Hägglöf describes his first report from Moscow to Undén dated November 1, 1946, which was not entirely liked by Undén. Hägglöf was promptly summoned to the Foreign Minister for a personal discussion, during which it became all the more clear to Hägglöf what views the Foreign Minister really held.

If the point of departure and the belief was that Wallenberg was dead, it was easier to pursue Undéns political line of Sweden functioning as a real go-between between East and West. To attain such a position, no serious problems could exist in bilateral relations. That was the cynical view of the Swedish Foreign minister Undén. It is obvious, to judge from the Gunnar Hägglöf’s memoir, that Hägglöf disagreed with his boss, whom Hägglöf considered “too naïve” on the subject of Soviet Union. Less than a year after Hägglöf’s appointment in 1946, he was removed from Moscow to the post as Sweden’s representative to the United Nations. As his successor was appointed a real ideological friend of Foreign Minister Undén, namely Ambassador Rolf Sohlman, who held the post in Moscow for seventeen long years thereby heavily influencing the Swedish foreign policy in relation to the Soviet Union.

It could be said that from the very outset of his service in Moscow Staffan Söderblom mishandled his efforts to clarify the question of Wallenberg’s fate with the Russians. Stalin most likely suspected Wallenberg of having been involved in some type of espionage activities, possibly on behalf of individuals or groups opposed to Soviet aims in the aftermath of the World War II. For these suspicions and for the inability of the Swedish Foreign Ministry and its envoy in Moscow Raoul Wallenberg had to pay with his own life. It was maintained from the Soviet side that he died, or was even deliberately executed on July 17, 1947. This was more or less regarded as the final status of the Wallenberg case, but was called into question by the discovery of the information about as yet unidentified “Prisoner no 7”, in the Lubyanka/Lefortovo prisons on July 22-23, 1947. Many have hoped or wondered if Wallenberg was kept alive in some remote Soviet camp later to be utilized in any kind of

“prisoner exchange”.

Do we know anything more about Swedish-Soviet efforts to arrange an exchange between Wallenberg and some other important person? Of course the first thought goes to a possible exchange between Wallenberg and the most predominant Soviet spy in Sweden for centuries, Colonel Stig Wennerström. The Soviets wished for sure to exchange him, but Sweden was not “playing the game” – on moral grounds (as mentioned above).

Besides the efforts mentioned above (involving the Soviet spy Stig Berling in 1979, where Sweden did play “the game”; and the possibility of utilizing the grounded Soviet submarine U 137 in 1981), it is interesting to read what Olof Frånstedt, the former head of the Counter Intelligence Service (Kontraspionaget) at the Swedish Security Police (SÄPO) writes in his memoir, which was published in two volumes (2013-2015) Hunter). I have also spoken to him directly several times, in joint efforts with some former colleagues, to finally disclose the heavy KGB/GRU/ID/STASI-infiltration of Sweden from the 1960s onwards. Ordinary Swedish people would never grasp the intimate close and secret contacts that existed between Swedish officials and NKVD/KGB/ GRU agents of different kinds. Like me, Frånstedt is convinced that this kind of infiltration into the highest strata of the Swedish society, including the diplomatic and political establishment, really sealed Wallenberg’s fate. The Soviet intelligence establishment NKVD/KGB was essentially influencing the handling of the Wallenberg case by remote control.

The diplomatic level was only one of several contact areas between Sweden and the Soviet Union. Another channel for secret – or shall I say – even illegal contacts – between the Social Democratic Party/Government and the Soviet Union was through the local KBG/GRU/STASI-officers or the ”rezidents”, as they are called. The chief of the respective Soviet/EastGerman/Czech, etc. intelligence service was named the ”Resident”(”rezident”) and belonged to the official Embassy staff in one capacity or another. But his or her main task was to establish and maintain either open or clandestine contacts with key people in the Swedish society who could be won to work for Soviet aims. “Communism” was not too far from “Socialism”.

It is impossible to recount here in the confines of this presentation the complex story of the highly secret Social Democratic espionage bureau, the so called IB (Informationsbyrån, Information Bureau), that existed within the Swedish Defence Staff from the 1950s -1970s). It’s primary aim was safeguarding the survival of the Social Democratic establishment in all potential future political, military or other circumstances. It was a secret intelligence construction that existed alongside and above the official Swedish intelligence agencies, like the Swedish Security Police (SÄPO), one of the IB’s main targets/opponents. Most notably, the Information Bureau maintained secret and regular contacts with the KGB officers and often the KGB ”rezident” himself, which was of course a most unsuitable liaison to maintain.

It is now known that highly placed Social Democratic politicians and functionaries, along with representatives of the mass media, worked for the IB in one capacity or another. The two most famous of these were the senior diplomats Anders Thunborg and Pierre Schori, both serving as International Secretaries of the Social Democratic Party from the 1960s onwards. Both advanced to high ministerial or governmental posts in subsequent years. Both served as Swedish Ambassador to the United Nations, for instance. Anders Thunborg advanced even further, to the post of Minister of Defence as well as Swedish Ambassador to both Washington and Moscow. In 1982, Pierre Schori, a close friend of Fidel Castro and an admirer of Che Guevara, became Secretary General (kabinettssekreterare) at the Foreign Ministry (where I served as the Chief Legal Adviser together with him). He was also a member of different Social Democratic governments.

Notwithstanding all this, both men met the KGB Resident at regular intervals. After each meeting they reported in writing to the head of the IB (the Social Democrat Birger Elmér) what had been discussed during these meetings. Thus there exists first-hand documentary proof of these inappropriate exchanges between high functionaries of the governing Social Democratic Party and Soviet Intelligence officers. During these meetings the Wallenberg case was also briefly discussed.

But mainly the Wallenberg case was not discussed, which shows that the Social Democratic Party apparently never used these very important KGB-channels to try to influence the Soviet Union or gain information about Raoul Wallenberg. The IB-documents that are at hand (most of these documents are either destroyed or remain still classified but should reveal much if they are made public) verify that Wallenberg’s situation was not discussed through these KGB

contacts, which have been the most effective way to facilitate a discussion between Sweden and the Soviet Union about Wallenberg’s whereabouts, his fate and possibly seeking his release from Soviet imprisonment. Apparently nobody cared to do so.

To the contrary, one can read, with total dismay, that on June 15, 1965, during a lunch meeting with Anders Thunborg at the Restaurant Metropol in Stockholm (between 13.00- 14.45), the Soviet KGB Officer (Streltsov) roundly criticizes the Swedish Prime Minister Tage Erlander for daring to raise the Wallenberg case with the Soviet Prime Minister Alexey Kosygin (during Erlander’s second state visit to the Soviet Union in June 1965). Erlander’s approach transformed the atmosphere at the talks into an almost threatening situation, with Kosygin leveling accusations against Erlander for again bringing up the Wallenberg question, as he also had done during his first visit in 1956 (see above).

The KGB-officer (acting Resident) Streltsov was clearly irritated: “It was disagreeable that the Prime Minister once more had brought up the Wallenberg case. Streltsov did not continue the discussion regarding Wallenberg, but noted that the Prime Minister at least did not this time raise all the other disappearances (the fishing boat crews etc). You Swedes, Streltsov continued, must understand that millions of people died or disappeared in the Soviet Union during the war.” Streltsov added that for this reason, it is not always so easy from the Soviet side to understand all these persistent questions about the disappearance of some few persons.

So, this was a really irritated and utter dressing down of Anders Thunborg, who – instead of making the point that the Soviet Union had illegally detained a Swedish diplomat –

did not say much more but turned to the next subject on the agenda. Thunborg made no further efforts to support or defend Prime Minister Erlander’s efforts to win clarity about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate as part of the top level talks in Moscow.

But while the Swedish government squarely carries the blame for its catastrophic handling of the Wallenberg case, what about Wallenberg’s own family? The mighty Wallenberg dynasty with its Stockholms Enskilda Bank, which by a fusion 1972 with Skandinaviska Banken became Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), steering and controlling a substantial part of Sweden’s financial and industrial sphere. Apart from the investigations performed by Raoul Wallenberg’s closest relatives, much was really not done by the mighty family Wallenberg. Why? A good answer is that Raoul Wallenberg (born 1912) did not belong to the inner circle of the Wallenberg dynasty that controlled the bank. In this regard also the Russians did miscalculate the willingness of the Bank Dynasty to extend its help to the more distant relative Raoul Wallenberg, who never came to work for the bank itself. But there could also be other unknown reasons for its passivity (see below).

The influential directors of Stockholms Enskilda bank (from 1972 Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken) the brothers Jacob Wallenberg (1892-1980) and Marcus Wallenberg (1899-1982) were only first cousins to Raoul Wallenberg’s father Raoul Oscar Wallenberg, who died from cancer three months before his son Raoul was born. Young Raoul’s mother Maj Wising (1891-1979) remarried in 1918 Fredrik von Dardel (1885-1979, with whom she had the son Guy von Dardel (1919-2009) and the daughter Nina Lagergren, née von Dardel (1921-). It is mainly through the half-brother and half-sister of Raoul Wallenberg, and their families, a continuous research has been going on regarding the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, i. a. in the form of “The Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtable – Guy von Dardel Memorial Meetings” (Budapest 2016 and Stockholm 2017).

In addition to what has been said in my presentation at the Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtables in Budapest 2016 and Stockholm 2017, I am further touching upon the Wallenberg case in my 2012-2019 published four volumes of Dagbok från UD (“Diaries from the Foreign Ministry”) dealing with the work of the Soviet Intelligence agencies NKVD/KGB, GRU, ID (the International Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party) and other Eastern Intelligence Agencies (i.a. STASI) to infiltrate the Swedish Government, the Foreign Ministry, the media and the political parties. I am in this regard basing my research i.a. on documents from the Mitrokhin-, Bukovsky- and CIA

Archives, as well as from information and debriefings of KGB-officers defected to the West. One of these being the KGB Colonel Oleg Gordievsky, who defected from the Soviet Union to the UK in July 1985, after which he was debriefed by the UK MI6 and the Swedish SÄPO (by the Counter Intelligence Unit of the Swedish Security Police).

KGB Colonel Oleg Gordievsky, born 1938, was at first a successful KGB officer with several key positions as chief of KGB Residenturas in different countries until he in Copenhagen turned into a higly influental KGB-MI6 double agent. In July 1985 he finally succeeded to defect to the UK via Finland much as a result of the revelations of Adrian Aimes, a high- ranking FBI officer working for the KGB. Gordievsky was KGB-officer in Copenhagen 1965-1970 where he was engaged by MI6 as a double agent. After another period in Copenhagen 1972-1978 as Deputy Chief of the KGB Residentura he was moved to London as Acting KGB Resident from 1982 until 1985, the year he was called back to Moscow for interrogations. In July 1985 MI6 took him out of the Soviet Union via Finland after which he was debriefed by several Western intelligence Agencies, also the Swedish SÄPO, to which he disclosed interesting names.

Together with the British professor Christopher Andrew in Cambridge Gordievsky published several important books about KGB and its operations in different countries. Gordievsky ́s defection to the West led to the disclosure of several Soviet agents and spies as well as to the breaking up of spy-rings in many countries, not least in Finland and Sweden. His reliability is therefore strong. What he has been telling Western intelligence units about KGB has proved to be very accurate.

In August 1997 a book written by Oleg Gordievsky and the journalist Inna Rogatchi with the title ”A Blind Mirror” (Sokea Peili) was published in Finland and in Finnish. Since I cannot read Finnish I am much indebted to my Finnish colleague ambassador professor Alpo Rusi for his permission to use his English translation (done in 2019) of the Finnish text as well as his references to Finnish conditions and circumstances, which much resemble, or are even identical with Swedish conditions and circumstances.

In Gordievsky’s – Rogatchi’s book of 1997 a number of Finns were labeled for their connections with the KGB and the GRU. In connection of the Skripal poisoning case in March 2018, a member of Russia’s Duma explained in a British newspaper that ”in case we would like to eliminate somebody as a traitor, his name is Oleg Gordievsky”.

For Finland, the head of the Finnish security police (SUPO) Seppo Nevala (Social Democrat, SDP) was fully aware of the problems Gordievsky’s revelations contained from the point of view of Finland’s national security. He was nervous about any debate it would trigger off in the Finnish not to say international media. Actually SUPO had received a message of evidence about espionage allegations related to Finnish citizens among whom a number of politicians and diplomats as well as business people from foreign intelligence agencies like U.S. CIA, German BND and British MI6 earlier during the 1990s.

Nevala was nervous in vain because ”A Blind Mirror” caused problems only for its authors. Their credibility was questioned even at the highest political level and in addition to this the publisher destroyed the manuscript which contained additions and corrections by the authors. The authors lost in the court against the publisher (WSOY) concerning the compensation of 126 000 Euros for the destroyed manuscript which most probably contained ”hot names”.

Although the public debate about the book died before it really started, the politicians got angry and the book was a hot topic among them in Helsinki and then finally withdrawn. Not

so many had time to read the controversial book before it was recalled from market. But suppose that the frank and outspoken text of the defected KGB-Colonel actually contained the truth about the eternal Wallenberg drama, as it also disclosed truths about the Finnish Prime Minister Kalevi Sorsa as well as other Finnish and Swedish politicians (e g Olof Palme), diplomats and civil servants. One must however underline the crucial factor of “trust or distrust” in Gordievsky ́s disclosures in his book of 1997. Do you have confidence in a defected former KGB-agent or not? But are there actually reasons to distrust Gordievsky? And suspect that he invented all this? Why should he lie? And if his “story” goes well together with similar stories from personalities of NKVD/KGB/GRU like Pavel Sudoplatov, Madame Kollontai, the Soviet ambassador in Sweden, Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina, Boris Yartsev and Vasili Mitrokhin (the Mitrokhin Archives in Cambridge).

The most sensational disclosure by Gordievsky in his and Inna Rogatchi’s book A blind mirror is related to the everlasting Raoul Wallenberg mystery and to his relative the Bank Director Marcus Wallenberg (senior), the brother of Jacob Wallenberg. If trusting the information that Gordievsky provides in his book the mystery of Raoul Wallenberg should at last be finally solved. It is almost hard to believe! What Gordievsky discloses are the following not very glorious circumstances:

There are several segments in the Gordievsky’s book about the importance of the Wallenberg family, in the forefront the two brothers Marcus Wallenberg (senior) and Jacob Wallenberg. Stalin was eager to collaborate with the Wallenbergs in all possible ways – in the building up of the Revolutionary Soviet Union lacking everything, especially money, iron and steel. This collaboration could very well, if it could not be arranged in a “normal friendly way”, be forced ahead, even by pure pressure and blackmailing. It is against this background that Gordievsky in his book insists that Marcus Wallenberg had an affair with the Soviet NKVD- agent Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina. NKVD was as said the Soviet espionage and security police preceding KGB, which was formerly established already 1917 and lasted until 1993 but under different names like GPU, OGPU, NKVD, GUGB, NKGB and MGB, nowadays FSB and SVR.

Gordievsky repeats on page 336 in his book “A blind Mirror” that Zoya Voskresenskaya- Rybkina had an intensive relationship with Marcus Wallenberg (senior). Following this embarrassing and highly risky affair – exposing Marcus Wallenberg (senior) and his Enskilda banken to the Soviets and the NKVD-forces, Gordievsky insists that Raoul Wallenberg became the victim of a NKVD recruitment effort which went wrong and therefore was poisoned in 1947 (like the GRU-MI6 double agent Skripal who was poisoned in Salisbury as late as 4 March 2018). Poisoning became the Soviet special liquidation method for defected KGB/GRU-officers or for persons having been the object of failed recruiting efforts. Such persons knew too much and had to be liquidated.

The NKVD-agent Pavel Sudoplatov, the agent Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina’s superior and one of the highest Soviet intelligence officers on the nuclear field (i a the Manhattan Project) and who organized the liquidation of Trotsky in Mexico 1940, provides details about the poisoning of Wallenberg in July 1947 in his book Special Tasks – the memories of an Unwanted Witness – A Soviet Spymaster (1994) , an extremely interesting memory of Stalin ́s spymaster who in the power struggle after Stalin’s death 1953 fell together with the NKVD chief Lavrentij Beria, barely survived from being executed (as Beria was), sentenced to fifteen years in prison 1953-1968 which he survived. The Prologue of his memories begins with these horrifying words (pp 2-5):

“My name is Pavel Anatolievitj Sudoplatov, but I do not expect you to recognize it, because for fifty-eight years it was one of the best kept secrets in the Soviet Union. You may think you know me by other names, the Center, the Director, or Head of SMERSH (the acronym for Death to Spies), names by which I have been misidentified in the West. My Administration for Special Tasks was responsible for sabotage, kidnapping and assassinations of our enemies beyond the country’s borders. It was a special department working in the Soviet security service. I was responsible for Trotsky’s assassination and, during World War II, I was in charge of guerilla warfare and disinformation in Germany and

German-occupied territories. — I was also in charge of the Soviet espionage efforts to obtain the secrets of the atomic bomb from America and Great Britain. I set up a network of illegals who convinced Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilar, Bruno Pontecorvo, Alan Nunn May, Klaus Fuchs and other scientists in America and Great Britain to share atomic secrets with us”.

Robert Conquest, the wellknown author and expert on Russia (his book The Great Terror), says in his Foreword to Sudoplatovs’s book that “this is the most sensational, the most devastating, and in many ways the most informative autobiography ever to emerge from the Stalinist mileu. It is perhaps the most important single contribution to our knowledge since Khruschev’s Secret Speech”.

It is significant that it is this High-Rankning secret NKVD-official, standing close to Stalin and Beria, that also gives a surprisingly detailed account in chapter 9 of this book with the title “Raoul Wallenberg, Lab X and Other Special Tasks” (pp 265-284). But let us come back to that chapter about Raoul Wallenberg and first introduce the key person in relation to Marcus Wallenberg, namely the NKVD-agent Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina.

On page 266 Sudoplatov talks about his subordinate NKVD-agent Zoya Voskresenskaya- Rybkina “as a classic Russian beauty, who spoke German and Finnish fluently”. To be added to the complexity of the situation Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina became married to the NKVD-representative in Helsinki and then Stockholm Boris Rybkin (alias Yartsev). Sudaplatov again (p 266): “My good friend Colonel Rybkin, first secretary of the Soviet mission in Finland before the war under the name of Yartsev (author’s note: in Swedish Jartsev), arranged that transfer (of 500 000 US dollar to the Small Farmers party). Stalin personally instructed him how to deal with NKVD agents of influence in Finland. During the war years, Rybkin and his wife were residents in Stockholm “.

For the sake of clarity let us quote what the Russian Wikipedia states about Sudoplatov’s close collaborator the NKVD Agent Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina or Zoya Yartseva, “the classic Russian beauty”:

Zoya Ivanovna Voskresenskaya (Russian: Зоя Ивановна Воскресенская; in marriage – Rybkina, Рыбкина; April 28 [o.s. 15], 1907, Uzlovaya, Tula Governorate, – January 8, 1992, Moscow, Russian Federation) was

a Soviet diplomat, NKVD foreign office secret agent and, in the 1960s and 70s, a popular author of books for children. A USSR State Prize laureate (1968), Voskresenskaya was best known for her novels Skvoz Ledyanuyu Mglu (Through Icy Haze, 1962) and Serdtse Materi (A Mother’s Heart, 1965). In 1962-1980 more than 21 million of her books were sold in the USSR.

In the late 1980s, as Perestroyka incited the wave of declassifications, Zoya Voskresenskaya’s story was made public. It transpired that a popular children’s writer was for 25 years a leading figure in the Soviet intelligence service’s foreign department. Voskresenskaya’s war-time memoirs Now I Can Tell the Truth came out in 1992, 11 months after the author’s death.

Zoya Voskresenskaya was born in Uzlovaya, Tula Governorate, into the family of a railway station master’s deputy, and spent her early years in Aleksin. Her father died when she was ten and mother with her three children moved to Smolensk. At 14 Zoya started working as a librarian, at the 48th Cheka battalion of the Smolensk Governorate. Two years later, in 1923, she was commissioned as a tutor and politruk to a local corrective labor colony for young offenders, then got transferred to a regional CP office in Smolensk. In 1928 Voskresenskaya moved to Moscow and in August 1929 joined the OGPU foreign office. Her first port of call in 1930

was Harbin in Manchuria; after two years of reconnaissance work she was moved to Riga, Latvia,

then Germany and Austria.

In 1935 Voskresenskaya started working in Helsinki, under the guise of ‘Irina’, an Intourist official, as a Soviet secret agent, in a tandem with an Embassy councilor (and NKVD Colonel) Boris Rybkin (alias Yartsev) whom she soon married. As the Winter War broke out, Zoya Voskresenskaya returned to Moscow where in the course of the next several years she became one of the Soviet Intelligence service’s leading analysts, coordinating the work of several residential groups, including Rote Kapellein Germany. In 1940, in secret report she informed Iosif Stalin of the impending Nazi Germany invasion.

As the Great Patriotic War broke out, Voskresenskaya joined the Pavel Sudoplatov-led group preparing saboteurs and partisan war leaders to be sent to the occupied territories. The first ever reconnaissance unit launched to the USSR Western border was trained by her. Voskresenskaya was preparing to be sent to the occupied territories, under the guise of a railway station guard, when in the late 1941 she and Rybkin were sent to Sweden where (as ‘madam Yartseva’) she joined the Soviet embassy as ambassador Alexandra Kollontai’s press attaché. As a secret agent she continued to coordinate various reconnaissance groups and individual agents, collecting data concerning the Nazi Germany’s transport maneuvering next to the Swedish border. Both women, working in close co-operation, were later credited for the fact the Sweden remained neutral throughout the war while Finland quit the coalition and in September 1944 signed the peace treaty with the USSR.

After the war Voskresenskaya continued working in Moscow and in the late 1940s became the head of the Soviet Intelligence’s German department. In 1947 her husband Boris Rybkin died, allegedly in a car crash near Prague. Voskresenskaya refused to accept official version, but failed to get the permission to investigate the case personally.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, wide-scale purges of the NKVD ranks started. Outraged with the arrest of Pavel Sudoplatov, Voskresenskaya spoke out openly to defend her former boss. Almost instantly she received the retirement orders but asked for the special privilege to remain an NKVD officer and was sent to a Vorkuta labour

camp as a head of a minor department, in the rank of lieutenant. In 1955 Voskresenskaya, in the rank of Interior Ministry colonel, retired from service and embarked upon the literary career. Writing for children, she made herself quite a name in the 1960s.

In the late 1980s, with most of the Stalin era’s Intelligence documents declassified, the story of Voskresenskaya was made public. Already terminally ill, she started writing memoirs. Teper Ya Mogu Skazat Pravdu (Now I can Tell the Truth) came out in 1992, 11 months after their author’s death on 8 January of that year. She was buried at the Novodevichye Cemetery”.

Much information comes out from her own book from 1991 Now I can Tell the Truth. In Gordievsky’s book of 1997 (together with Inna Rogatchi) much material is found about the NKVD/KGB in Sweden which reveals that Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina, who was in Stockholm as NKVD representative with her husband Boris Yartsev, gave NKVD the tip that Raoul Wallenberg should be recruited for NKVD and sent to Stockholm because she had created a close contact with Marcus Wallenberg (senior). However in that “game” the young Raoul Wallenberg was the card that didn’t play the game – Marcus Wallenberg and Raoul Wallenberg were too distant from each other – and therefore Raoul was eventually poisoned in Moscow in 1947 because he did not want to cooperate with NKVD. This was the usual fate that waited failed NKVD/KGB-recruitments. Because of his refusal to become a NKVD agent in his own land he was doomed by Stalin (and Molotov) to die.

On pages 116-122 of ”A Blind Mirror”(Sokea peili) Gordievsky explains his conversations with Zoya during winter evenings in Moscow in 1980. Gordievsky had a meeting with Zoya Rybkina 1980 after she only was the author of childrens’ fairy tales and used the name Vosenskaya. She is also known perhaps for the Swedish SÄPO as Aleksandra Rybkina who arrived in Stockholm in 1941. Gordievsky says:

1. ”Zoya was an exotic beauty whose sensual attractiveness was used by NKVD for strategic operations” (p.117)

2. ”Let us take as an example, Zoya’s achievements in handling Marcus Wallenberg in a remote hotel in Saltsjöbaden during wonderful weekends. These weekends led to a favorable trade deal between the Soviet union and Finland which contributed favorable to the capital of Wallenberg”(p.117).

3. ”First of all she was hard and skillful and was promoted to run in the rank of colonel the department of Austria and Germany after the end of war”(p 118).

4.”Zoya was former case officer of Hella Wuolijoki. After 50 years she told Gordievsky that she considered Hella a reliable spy but her husband Boris Yartsev did not. Today (1980) I can say that I was right (says Gordievsky in his book)… In Stockholm Zoya approached with the help of the Wuolijoki family Niels Bohr (nuclear researcher) in order to get information about nuclear matters…it is a well know secret in the KGB that Zoya Rybkina had a collusion against madam Kollontai, the ambassador of the Soviet Union in Stockholm 1930-1945, who lost her career 1946 as a result of Zoya’s operations. It is also believed that Zoya was able to destroy Kollontai’s diaries 1946”. (p.118)

5. ”It is also a well kept secret inside the KGB that Zoya’s activities in Sweden and closeness to Marcus Wallenberg made her the ”bad spirit” for Raoul Wallenberg and that she informed NKVD about Raoul Wallenberg’s activities in Budapest and possible connections to the United States Intelligence Agency OSS (Office of Strategic Services), an organization that was established in 1942 during the War and preceded CIA, which was established in 1947. And NOTA BENE she managed to get Stalin to approve the operation to capture Raoul Wallenberg with the aim to recruit him for NKVD. The KGB sources refer to this operation as a reason to promote Zoya after the war” (p.119). As is clear from what Sudoplatov writes in his book Special Tasks Stalin was really convinced that Raoul Wallenberg was an agent for OSS and acted accordingly (see below).

As to the reliability of the KGB-MI6 Double Agent Oleg Gordievsky – who himself as a Double Agent MI6-KGB during the NATO exercise Able Archer 1983 with the NATO nuclear forces prevented the outbreak of a real “Nuclear War” between USA/NATO and the Soviet Union – has not been labeled as a liar or somebody who would have lied all this. In his book of 1997 he says that the Swedish government has preferred to have good relations with Moscow/KGB and not to make problems by reveal “too much”.

On page 337 Gordievsky states that he has explained all related to the Wallenberg case in the course of the years to the Swedish official authorities many times. The question may then be put: When and how has the KGB Colonel Gordievsky been talking to the Swedish authorities

about the Wallenberg case? Probably such talks could have occurred in connection with the debriefings held by the Swedish SÄPO after his escape 1985 to the UK. Gordievsky states that the only thing he would like to get as a compensation for his first hand information to the Swedes is that his role as an informant would be published. First hand information about KGB-Agents and KGB- Contacts!? Although the Swedes promised to follow his wishes in this regard, nothing has happened! The only thing Gordievsky has not been sure about is the way Raoul Wallenberg was executed. But in 1994 the NKVD-chief Pavel Sudoplatov in his memoirs explained that Raoul Wallenberg was poisoned 1947. Pavel Sudoplatov died in 1995, labeled as an old man who suffered of sclerosis.

In his book Special Tasks Pavel Sudoplatov places the activities of the NKVD-spouses “Zoya and Boris Yartsev” (as they were known in Stockholm) into the prevailing circumstances 1941, i.e. that the so called Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union had ended with the severe Moscow Peace Treaty of 12 March 1940 (p 265 et seq). Notwithstanding the peace treaty Finland found itself – after the breaking down of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939 – participating on Nazi-Gemany’s side in Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa, that is to say the German attack on Russia on 22 June 1941, which lasted until Stalingrad 1942-1943. During that period Finland’s government tried to sound out possibilities of a separate peace with Stalin, in which efforts Madame Kollontai, the Soviet ambassador in Stockholm, as well as the Swedish government participated. But not only them, but also Marcus Wallenberg and Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina (se further below).

Sudoplatov begins his chapter 9 with the title Raoul Wallenberg, Lab X and Other Special Tasks in the following way (p 265): “There are unsolved mysteries involving the Wallenberg family of Sweden. The best known is the case of diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who was arrested by Soviet military counterintelligence, SMERSH, in 1945 in Budapest and, I believe executed secretly in Lubyanka jail in 1947. The Wallenberg family had clandestine contacts with representatives of the Soviet government from the beginning of 1944, and while I was not involved with Raoul Wallenberg, I was aware of his family’s contribution to our making peace with Finland. The pattern of military counterintelligence reports on Raoul Wallenberg and the family’s connection made him a candidate for recruitment. His arrest, interrogation and death in Lubyanka all fit the pattern of a recruitment effort gone bad. Fear that the attempt to recruit him would be exposed if Wallenberg were released led to his elimination as an unwanted witness”.

Sudoplatov continues (p 265-266): “The Wallenberg’s relationship with the Soviet Union started in 1944, when our reszidentura in Stockholm was instructed to look for influential figures in Sweden who might act as intermediaries between the Soviet and Finnish governments to facilitate the signing of a separate peace treaty between Finland and the Soviet Union. Stalin was concerned that Finland, a German ally since 1941, would sign a peace treaty with the Americans that would not guarantee Soviet interests in the Baltic area: the Americans would not allow us to occupy Finland. In fact, we did not need to occupy Finland; we could keep it neutral through our agents of influence in all of the major Finnish political parties. These agents cooperated with us in return for a guarantee of the preservation of a neutral Finnish role in Europe – a bridge between the Communist and capitalist worlds. This is what came to be known as Finlandization in the 1970s and 1980s”.

Sudoplatov explains (p 266): “Rybkin, a tall, well-built man, had a sense of humor and was a good story teller. He and Zoya were popular on the diplomatic circuit, where one of their missions was to watch for German overtures for a separate peace deal with the United States and Britain without Soviet participation. They were also active in clandestine economic operations. In 1942 Rybkin arranged through an agent, the popular Swedish actor and satirist Karl Earhardt (Gerard), a deal to supply the Soviet Union with high-tensile steel for the aviation industry. We desperately needed that steel because our metallurgic plants were seized by the Germans in 1941 and our supplies from Siberia were unreliable. The deal was a gross violation of Swedish neutrality, but the Enskilda Bank, controlled by the Wallenberg family, profited handsomely from the exchange of the steel for Russian platinium”.

Sudoplatov continues (p 266-267): “The Wallenberg family was interested in a peaceful Soviet-Finnish settlement because its capital investment in Finland. Marcus Wallenberg (Raouls uncle; authors notice: not correct) maintained friendly contacts with Karl Earhardt, and the Center suggested that Earhardt should introduce Zoya to Marcus at a cocktail party”.

“Zoya charmed Marcus Wallenberg, and they agreed to meet again at a luxurious hotel owned by the Wallenbergs outside Stockholm at Saltsjöbaden. Zoya spent a weekend with Marcus Wallenberg planning how to bring together Soviet and Finnish diplomats so that the

terms of a separate peace treaty could be discussed. What was important, she said, was that Wallenberg convey to the Finns that the Soviet side would guarantee real neutrality for Finland with a quid pro quo of a limited Soviet military presence in the Finnish Baltic ports in the area of Porkala”. (italics added by this author).

“It took only a week for Marcus Wallenberg to arrange Zoya ́s first meeting in February 1944, with the Finnish ambassador to Stockholm, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, who later became president of Finland. Alexandra Kollontai, the Soviet ambassador to Sweden and our first woman diplomat, joined the talks under instruction from Stalin and Molotov. The consultation continued throughout the summer of 1944, and on September 4 a treaty was concluded. TASS reported that the government of Finland had severed its alliance with Hitler and signed an armistice agreement with the Soviet Union”.

The Finnish Professor Tuomo Polvinen confirms in his biography of President J.K. Paasikivi that Marcus Wallenberg paid a visit to Helsinki in February 1944 which was organized by Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina in order to consult about peace options. Marcus Wallenberg had a lunch with President Risto Ryti and Foreign Minister Henrik Ramsay on 6 February 1944 in Helsinki in the middle of heavy bombings. Before that the ambassador of the Soviet Union in Stockholm Madame Kollontai had had a lunch with Marcus Wallenberg in Stockholm for launching a secret link via him to the Helsinki government about peace negotiations with Moscow. However the real operator of this scenario was Zoya Voskresenskaya-Rybkina who was the person that organized Marcus Wallenberg’s lunch with Ryti in Helsinki 6 February 1944.The two ladies were as said competitors. In 1949 Marcus Wallenberg was awarded the Grand Cross of Finland’s most high ranking order, the Order of the White Rose, by President Paasikivi for his efforts to assist Finland during the Continuation War and the conclusion of the separate Peace Treaty on 4 September 1944.

Sudplatov continues (p 267): “Thus the detention of Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest in 1945 was not accidental. Stalin and Molotov wanted to blackmail the Wallenberg family; they wanted to use its connections for favorable dealings with the West. In 1945 the Soviet leadership was playing with the “Jewish issue”, cynically spreading rumors that an autonomous Jewish republic would be established in the Crimea, not Palestine, in order to mollify our British ally. I received oral instructions from Beria to plant such rumors in the talks I had with the American ambassador Averell Harriman when I met with him in 1945 under the cover name Matveyev. My speculation is that Stalin wanted Wallenberg recruited to assist in raising the international capital that Stalin hoped to attract for postwar economic reconstruction, using the bait of a Jewish homeland”. (italics added by this author).

“(p 267-268) At the time of his arrest by the Red Army in Budapest, Raoul Wallenberg was deeply involved in the evacuation of Jews from Germany and Hungary to Palestine. We knew he had a heroic image among world Jewish leaders. Wallenberg could not have been detained without direct orders from Moscow. If he was arrested accidentally, as might occur during the fierce fighting in Budapest, local SMERSH authorities were bound to report the incident to Moscow. Now it is known that Nikolai Bulganin, then the deputy commissar of defense, signed the order to detain Wallenberg in Hungary in 1945, and passed it on to Abakumov, head of SMERSH”.

“(p 268) After nearly half a century of fruitless investigations by KGB officials and journalists, the file on Wallenberg is now said to have mysteriously vanished. One of my former colleagues, Lieutenant General Aleksandr Belkin, the deputy head of SMERSH, saw the files before they disappeared. He reported that in 1945 all rezidenturas of SMERSH received an orientirovka (briefing) identifying Wallenberg as an established asset of German, American, and British intelligence. The instructions were to continuously report Wallenberg’s movements to Moscow and to assess and study his contacts with German authorities, both national and local”.